When a major incident happens that impacts people safety, we first think of our brave first responders – police, medics, firefighters and others that are always present to help ensure the safety of people and the environment we live in. Less visible are the tools, technologies and methods of communication that they use to help save lives and mitigate risk, often when seconds count.

As our world becomes more connected and our cities get smarter, governments, emergency services and even private organisations increasingly rely upon hundreds of new and existing technologies to help communicate during crisis.

To be truly effective, security and interoperability is key– but in many cases, systems and technologies have to comply with strict regulations and many communicate in isolation. Aside from being less effective, this is just poor economics – especially when organisations have so many existing channels, devices and other connected ‘things’ that can be used as part of an emergency response strategy.

How data can help and hinder a crisis

With connected devices in our hands, offices, homes, buildings and regional areas – we are sharing, collecting, analysing and monitoring data all around us. This data has the power to unlock ways for ‘Smart Cities’ to deliver more effective emergency management and business continuity plans, enhancing both safety and productivity. However, this must be balanced with potential risks to data and ultimately, peoples’ lives.

In any crisis, things can change in an instant. Misinformation or mass panic can spread quickly, impacting the ability for those with a duty of care to take correct action. Faced with social media rumours, jammed phone networks and general confusion in an information vacuum – this can be a monumental challenge to manage for any decision-maker with a duty of care.

So how can ‘Smart’ nations address the complexities and costs of next-generation crisis management, compliance obligations and a changing threat landscape to keep people safe? Properly designed crisis communications programs can help in this context.

Getting ahead of the noise – with real-time trusted information

Ultimately, the best way to manage people and emergency stakeholders in any given situation is to ensure the right message is getting to the right people from a trusted source; at the right time. Just as importantly, crisis communication systems must use authentication and encryption to secure all communication and comply with government security and privacy regulations.

To alert citizens and get ahead of misinformation, emergency teams need interoperable systems that will integrate with social media feeds – ensuring messages from a trusted source can be amplified to the public.

It’s a lot to think about, but to be effective, next generation crisis communications systems must provide real-time access to correct data, enabling secure communications between platforms and with those for whom they are designed to help. This not only applies to densely populated cities, but in regional and rural areas, where incidents such as the Australia’s2019 Queensland floods or the bushfires in Tasmania and Victoria have demonstrated the need for such systems.

With emergency responsibilities increasingly shared between various organisations, teams need to also ensure they can rapidly share data with everyone who has a direct or supporting role in a response. This could include pulling additional resources onto the scene, such as explosives experts, tactical teams, contaminant experts or health officials who may be off-duty or without access to their land mobile radio (LMR).

For example, as a result of the recent measles outbreak in New York, a state of emergency has been declared, demanding that unvaccinated people living in Williamsburg and Brooklyn must receive the measles vaccine – or face violations. This kind of response needs both a narrow geographic focus, such as certain areas in New York, and a potentially national range of incidence management to help contain it, such as afflicted people travelling through airports.

Managing a crisis is a two-way street

Crisis communications systems aimed at controlling an epidemic like this must be interoperable across a wide range of networks, media and devices used by different agencies, first responders and health professionals. It is also critically important to get information back from people in the field, such as health staff working with afflicted patients or emergency staff handling a new outbreak.

With two-way communication capability, it is easier to find out who needs help and how to co-ordinate people to assist. For example, geographically, you can know who’s available, nearby and contact them automatically. If team members are unavailable or someone doesn’t reply, it will automatically alert the appropriate people.

In the context of a ‘Smart City’, here is where secure multi-modal communication plays an integral role. By this, we mean the ability for a trusted platform to use many different methods of communication to alert, then get intelligence back from the field. This includes everything from PA systems, to connected security cameras, digital TV screens, PCs and the phones in peoples’ hands.

Stakeholders must be able to not only send out messages (sometimes targeted to specific people and locations), but also confirm and track responses. Likewise, in situations where emergencies may arise – from remote areas to mining sites and beyond – relying on a single mode of communication increases risk and heightens the chance of failure. With a campus the size of a small city, Macquarie University in Australia is a great example of how an organisation is putting this into practice, using BlackBerry AtHoc.

Government agencies already appreciate the importance of this capability. According to researchers, almost 70% of government agencies say giving first responders access to real-time data in the field is critical or very important, while nearly 80% want to easily communicate with state and local agencies in surrounding areas. Almost 75% want to connect personnel across different networks and devices.

These results demonstrate the promise of change. Collaboration between industries and sectors has traditionally been a challenge, with organisations protective of information or being bound by regulations prohibiting the sharing of data.

Collaboration: Smart Cities are better together

There is now an increasing realisation that working together, while continuing to protect data, is vital in responding to incidents effectively. With many countries applying ‘Smart City’ principles to improve the way we live and work, this means we are more connected to each other, to services, infrastructure and even political and private organisations.

At the same time, the rules for emergency preparedness are being re-written, influenced by new regulation and next-generation technologies and a changing world of threats. At the core of any smart city design– is privacy and security of data and the safety of employees and citizens. This starts with ensuring that government and private organisations have the appropriate systems, training and business continuity procedures in place to be both cyber-resilient and crisis-ready.

At the same time, the rules for emergency preparedness are being re-written, influenced by new regulation and next-generation technologies and a changing world of threats. At the core of any smart city design– is privacy and security of data and the safety of employees and citizens. This starts with ensuring that government and private organisations have the appropriate systems, training and business continuity procedures in place to be both cyber-resilient and crisis-ready.

Smart Cities undoubtedly introduce significant opportunities and risk – but the fundamental goal should always be to keep people safe while harnessing the efficiencies of the environment. Part of any strategy will be to ensure that next-generation communication systems are in place to ensure emergency procedures are keeping up with the pace of the threat landscape.

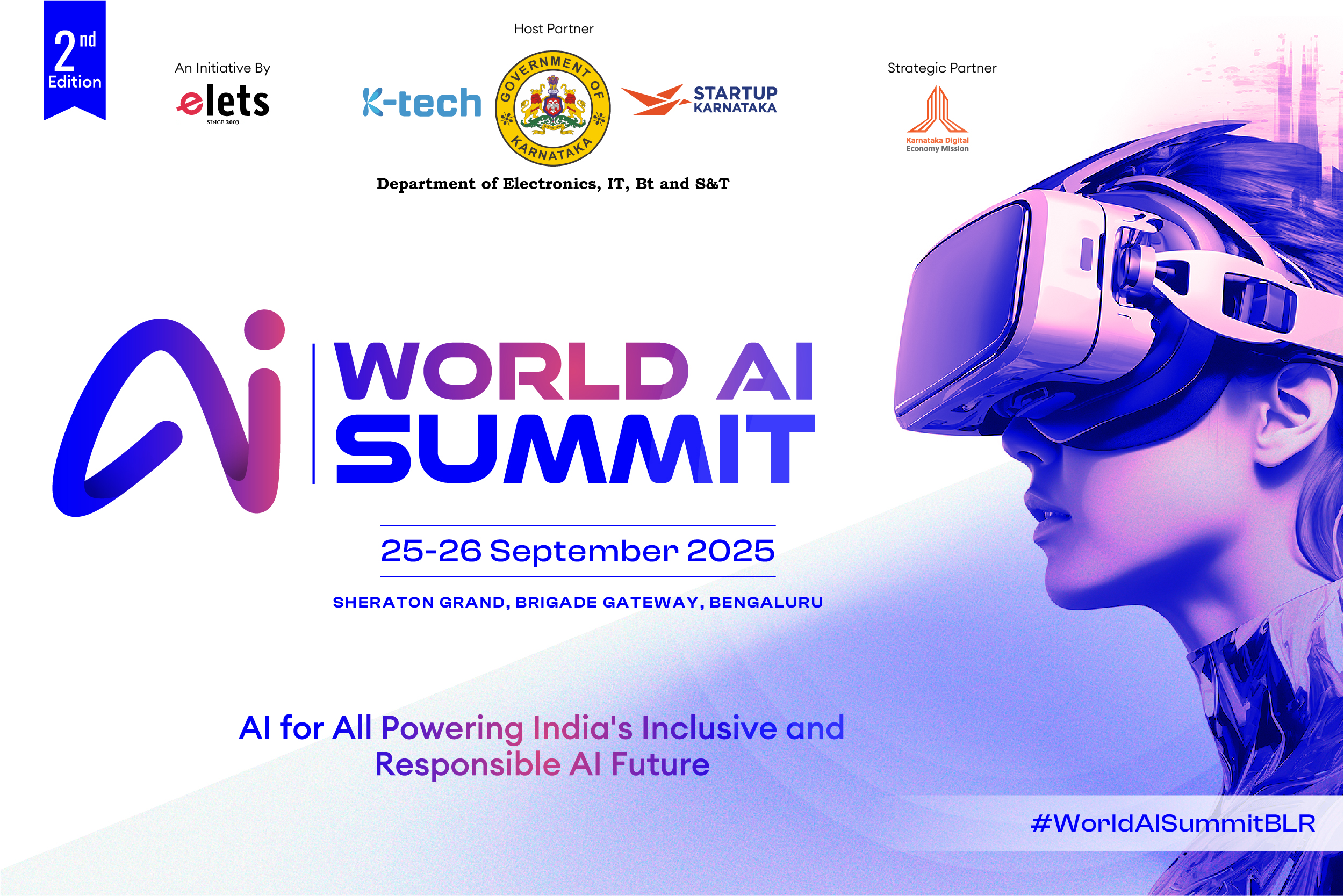

Be a part of Elets Collaborative Initiatives. Join Us for Upcoming Events and explore business opportunities. Like us on Facebook , connect with us on LinkedIn and follow us on Twitter.

"Exciting news! Elets technomedia is now on WhatsApp Channels Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest insights!" Click here!